ANNONCE

Appreciating Overformynderiet

After a thorough renovation, the distinctive building which formerly housed the Overformynderiet (Public Guardian Office) is cleaner and crisper than ever. Inside, the building has been updated with an approach one might well call functional functionalism.

Kristine Annabell Torp

Architect MAA and associate professor at The Royal Danish Academy

Overformynderiet – the Danish Public Guardian Office – was originally ready for its official inauguration in 1937. The building erected at Holmens Kanal in Copenhagen was an entirely novel creature at the time, based on a completely new form of construction in a Danish context: a steel frame cased in concrete. The architect Frits Schlegel turned the building into a celebration of the new technique, letting the concrete elements protrude in the building’s facades in rhythmic sequences that were not only determined by principles of construction, but also governed by the office divisions which the design programme was to facilitate. With this highly visible, rhythmic approach to proportioning, the building came to appear as a meeting between those last vestiges of neoclassicism by which Schlegel had been influenced at the School of Architecture run by the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and, on the other hand, the flourishing functionalist movement that informed the work of many of the young architects of the day. Schlegel would have preferred the recessed panels in the facade to be plastered in concrete, thereby giving the building a wholly uniform, undecorated appearance. This view was entirely line with the tenets of functionalism and with those of his role model Auguste Perret, the French pioneer of reinforced concrete, whose headquarters for the French navy in Paris was a clear inspiration for Schlegel. However, the client, meaning the authorities, had other plans for the façade. They decreed that the façade should be covered with marble to promote exports from the newly opened Greenlandic marble quarries. This did not please Schlegel, who was reportedly clearly unhappy at the opening party. Few today would agree with Schlegel. The marble cladding of the Overformynderiet has become an iconic part of Copenhagen’s cityscape and was, of course, a key challenge when it was decided that the building – which is listed as having high conservation value within Danish preservation regulations – should be renovated.

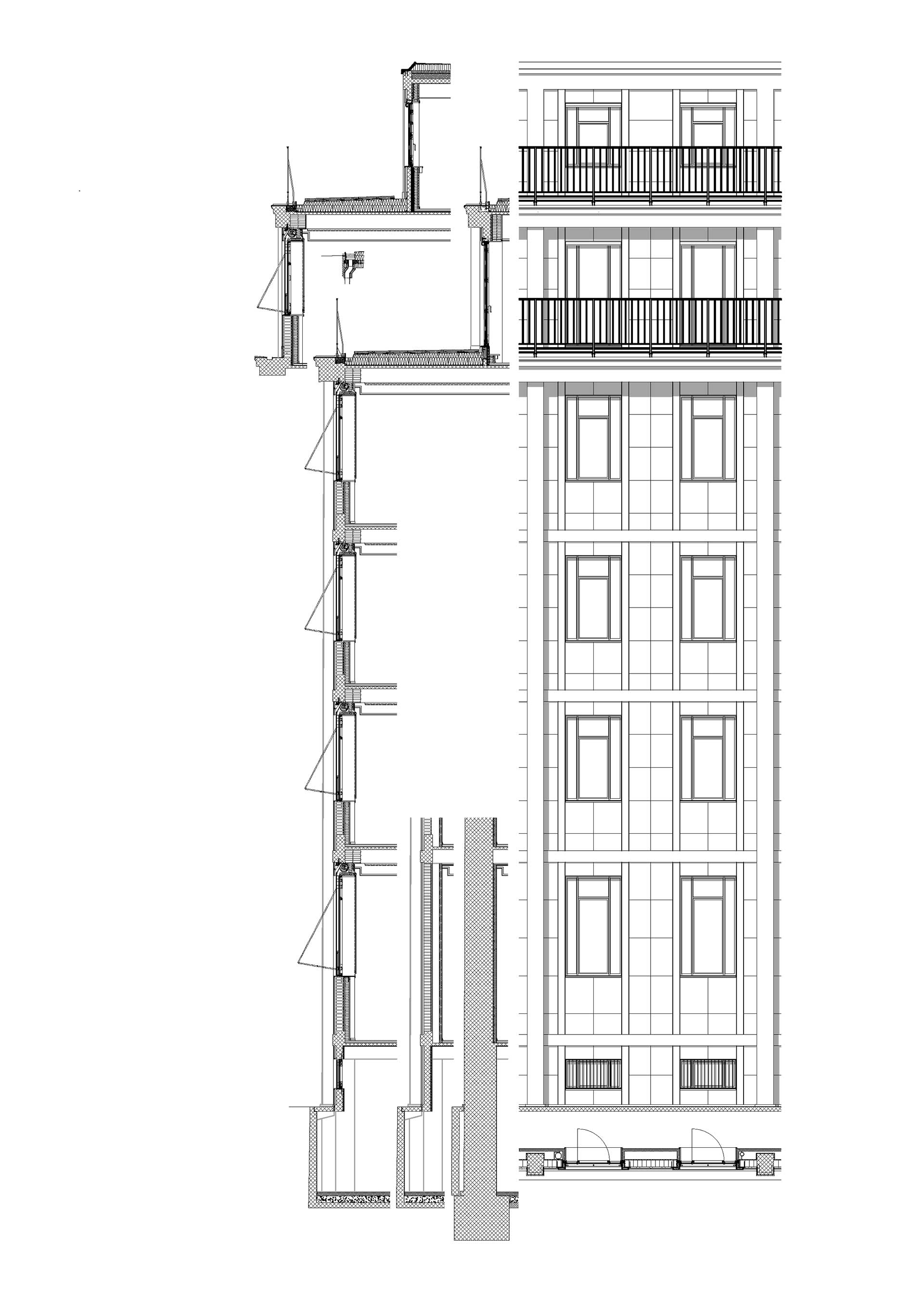

The building’s classification under Danish preservation laws meant that the façade renovation had to respect and adhere to the building’s original appearance. The first stage involved taking down all the marble cladding to facilitate renovation of the concrete structure. The latter task turned out to be a particularly extensive undertaking, one that included discoveries such as PBC paint which had to be removed and crumbling pillars that ended up being replaced with fibre-reinforced concrete. The result is a concrete structure that is as good as new, if not better. The several extra millions allocated along the way for what turned out to be an unexpectedly complicated renovation were also used to tidy up and remove various makeshift solutions that had been added over the years, especially on the roof and cornices. These were not only detrimental to the construction, but also to the building’s elegant profile. To remedy this, the team chose a special insulation solution – one that not only counteracted thermal bridges and condensation, but which also gave the opportunity to return the façade to its former simplicity by placing the insulation within the cavities of the facade. As an elegant, barely visible signature of ‘the major renovation of 2019’, the top edge of the roof has been given a forty-five-degree slant. A small and subtle gesture which cannot be seen close up to the building itself, but which shows up beautifully in profile when viewed from a distance.

The marble cladding presented problems of a different kind: many of the existing slabs were no longer fit for purpose, and obtaining more Greenlandic marble was no longer possible. A number of blocks of Greenlandic marble once used to fill in the port of Copenhagen and happily rediscovered during the excavation for the foundations of the Royal Danish Playhouse became part of the solution. More than anything, however, the so-called honeycomb technique was the decisive aspect that made it possible to source enough marble to cover the entire building. The method involves attaching extruded honeycomb panels with a hexagonal core to either side of the marble slabs, which can then be split in two. It sounds simple, but it most certainly is not. All the marble slabs were sent to Dallas to the only company in the world that masters the technique. The sojourn to America certainly paid off; the previously faded slabs have regained their colour, and the delicate veining of the marble is once again clearly visible.

Kristine Annabell Torp

Architect MAA and associate professor at The Royal Danish Academy

Interior remodelling:

Present tenants: The Danish Ministry of Employment and The Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities

Architects: Rørbæk og Møller Arkitekter

Team: Anders Wesley Hansen (partner), Troels Radmer Jensen, March Johan Rooijackers, Irina Maksimovich, Marthe Frey Eriksen, Bettina Strøyberg, Gökce Kitir, Jette Lynge Rasmussen and Jannik Kristensen

Client: The Danish Building and Property Agency

Engineer: Rambøll Danmark A/S

Art: Jette Hye Jin Mortensen (light installation in the main entrance towards Holmens Kanal 20)

Completed: 2019

Façade:

Architect: Bertelsen & Scheving

Architects (general consultant)

Team: Jens Bertelsen, Jesper Sort, Claus Nebelin, Jonas Vollmond, Sarah Due Larsen

Client: The Danish Building and Property Agency

Sub-consultant: Jørgen Nielsen

FRI – The Danish Association of Consulting Engineers

Completed: 2016

Original building

Architect: Frits Schlegel

Engineer: Ernst Ishøy

Completed: 1937

References

All references to Frits Schlegel, including those concerning the connections to Auguste Perret, are from Vibeke Andersson Møller’s book Arkitekten Frits Schlegel, published by Arkitektens Forlag in 2004.

Issue

This review was first published in Arkitekten 06/2020.

Translation

This article was translated from Danish by René Lauritsen

ANNONCE

Many may have noticed that the bolts which used to stick out through the marble in a grid-like series of dots all over the façade have disappeared. Instead, the mountings and holes are hidden behind plugs of Greenland marble that blend in with the rest of the surface. The decision to do this was subject to much discussion because the visible bolting had gradually become part of the building’s signature look and so was considered worthy of preservation by many. However, it was not part of the original façade, but a trait which arose after a facade renovation in 1963–64, overseen by Schlegel himself. Another striking feature of the façade is the red awnings, which have been part of the building all along and were reconstructed as part of the renovation. Furthermore, the dull aluminium windows introduced as part of a façade renovation in the 1970s have now been replaced with new, narrow-profile steel windows, which in terms of material and appearance come close to the building’s exquisite original windows.

The main door with its narrow brass frames also survived the transition to becoming a ministerial main entrance with all the requirements this entails in terms of security and automation. Above the front door is the vast sign so familiar to all Danes (it too a rather blatant reference to Perret’s marine building) – a striking visual reminder of a past when authorities were rather more overtly visible and when the Office of the Public Guardian managed the fortunes of the disenfranchised. It is very likely that those poor wretches who used to stand with their heads reverently bowed in the Overformynderiet public business room after having first ducked underneath the sign did not pay much heed to its spatial qualities. Still, it was a beautiful room, surrounded by offices two steps above its floor level, filled with daylight and with soft light filtering down from above through the glass bricks set in the atrium floor on the floor above.

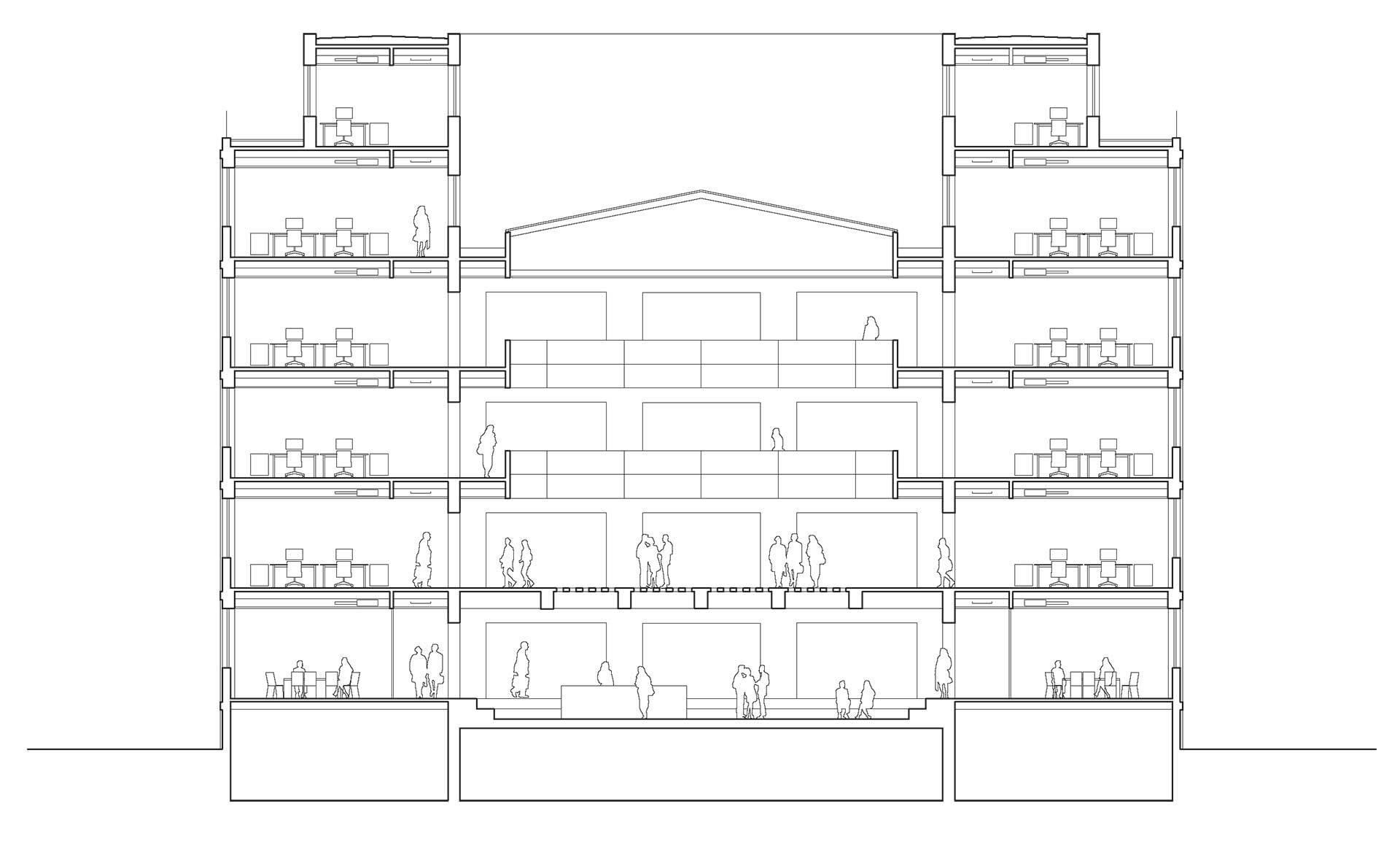

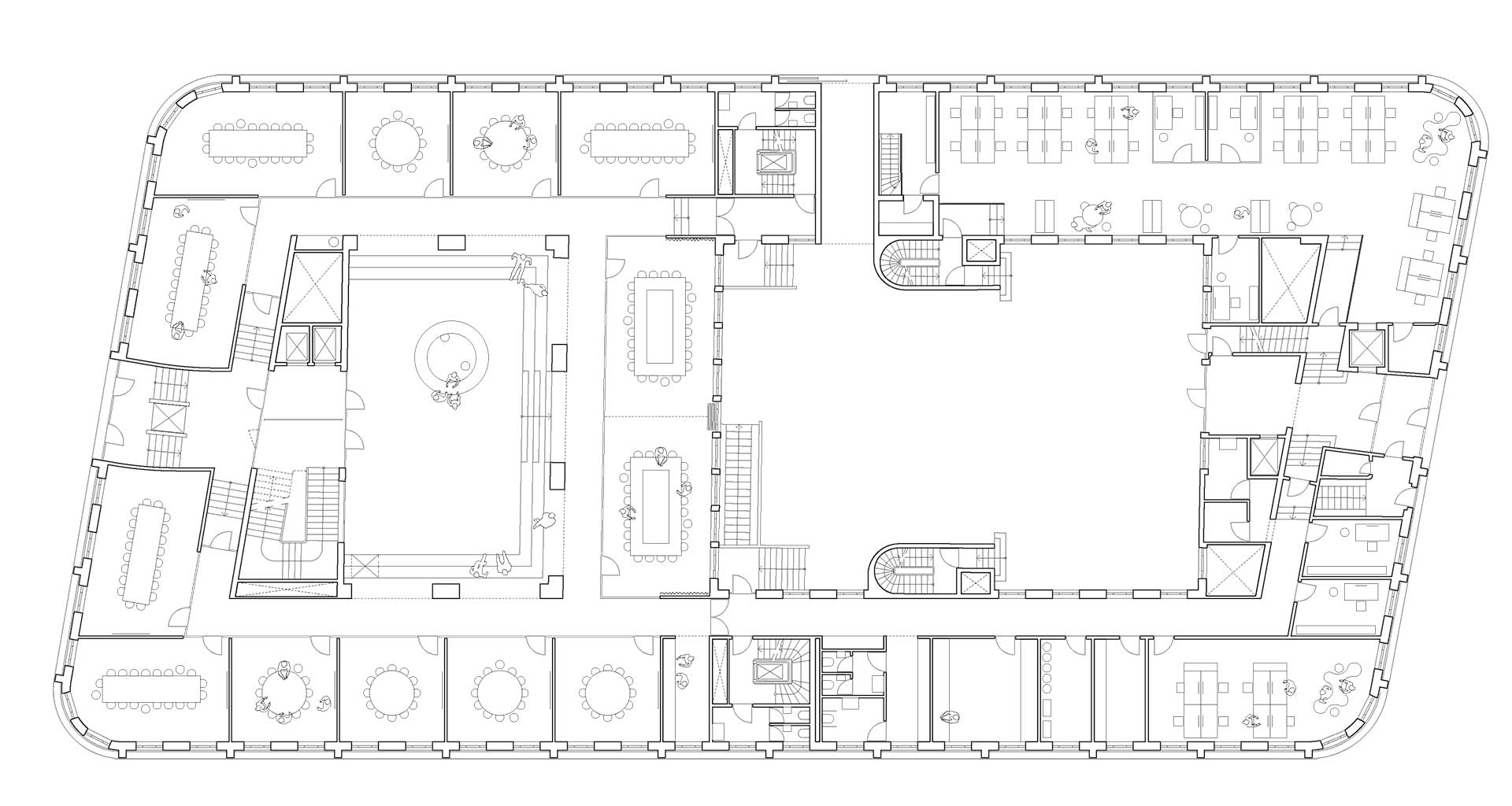

Over the years, successive tenants have treated the building interior in such a manner that an actual renovation was out of the question. The team behind it calls the process a revitalisation instead, and they were given free rein as far as the building’s interior is concerned after it had been stripped virtually bare. The former public business room now houses the building’s reception, still surrounded by offices and daylight, now supplemented by meeting rooms fitted with glass doors to make the most of the light. The change of level is framed by three deep steps covered with repurposed surplus wood, creating a setting for more informal meetings. These traits, together with the frameless glass doors, leave a clear 2019 imprint on the room. This should certainly not be taken as a criticism: overall, the project has succeeded in creating rooms which, throughout the building, possess a simplicity that continues in the vein of Schlegel’s elegant functionalism while catering to present-day demands for technology and sustainability. In addition to updated heating and ventilation systems, flexibility was an important parameter to promote sustainability: the rooms must be sufficient simple and robust to accommodate different functions and a succession of different office set-ups.

One might object that in certain places, this functional robustness comes across a little too strongly, but this is probably due to financial concerns. For example, it was not possible to recreate the building’s original, hand-laid black-and-white rubber floor, meaning that it now has cast floors of a less-than-thrilling kind instead. Likewise, installing anything other than standardised security doors on each floor was presumably out of the question, but even so the sight of such bulky aluminium doors opening up on Schlegel’s oak-lined atrium is rather jarring.

The atrium is and will always be the main showpiece of the building, and unlike the rest of the interior it was intact before the renovation began. Despite its unique character, or perhaps precisely because of it, the atrium had been largely ignored as a place of actual utility before the renovation. That situation has certainly been rectified: the space has now become the heart of the building. As one would expect, this has prompted a need for new connections in the form of several new apertures and passageways to create a flow of people and light. In a momentary fit of anachronistic nostalgia, one might entertain the quite paradoxical thought that there is something rather too functional about these new apertures leading to the atrium, framed as they are in white metal and entering into competition with the skylight. But from a rational, or let us say functionalist, point of view, it probably makes no sense not to do so. The bright office spaces on the outside of the square are now better connected to the atrium and, thus, also to each other. The revitalisation of Schlegel’s fine spatial layouts, as well as the development of a new schema for offices that involves alternating open and closed alcoves, has produced some fantastic office spaces, including the roof terraces on the recessed upper two floors where staff can enjoy their lunch with a splendid view of the city.

A number of details in the interior have also been preserved and renovated, reminding us once again of the importance of tactile details such as the solid wooden handrails on the stairs, the wall lamps in the atrium, a leather-covered sofa in the same place, the arched windows in the stairwell out towards the courtyard and a wood-lined elevator that not only takes us to another floor, but also to another time. Fortunately, we ourselves come from a time that appreciates what once was, and it is surely a a sign of a well-functioning and civilised welfare society to see so much money and so many skilled professionals being allocated to maintaining our architectural heritage.

Photo: Jens M. Lindhe

Facade section. Drawing: Bertelsen & Scheving Architects