ANNONCE

The Reunion of Function and Space

The original qualities of Friluftsskolen have been brought to light again – while accommodating the users’ present-day requirements for the use of its rooms.

Peter Thule Kristensen

Architect MAA, dr.phil., Ph.D. and professor at The Royal Danish Academy of fine Arts

Læs den danske version her.

The renovation of architect Kaj Gottlob’s famous open-air school – Friluftsskolen – from 1938 is an excellent example of a project that does not make a big deal of itself – which is precisely why it succeeds in bringing the listed, functionalist school building back to life after many years of inertia and inaction. The renovation was preceded by very extensive efforts to determine the building’s original state and condition – and by equally extensive negotiations between the architects, the City of Copenhagen in the role of client and the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces as the authority with regulatory responsibility for its conservation. The project shows the crucial role played by technical studies, evaluations and negotiations today – even when undertaking work that at first glance appears to be a gentle restoration returning the building to its original state. If you look more closely, the project is not just a restoration but rather a transformation that makes the original ‘recovery school for sickly children’, as it was known then, more suited to its present-day use as a school for children with mobility disabilities and other challenges.

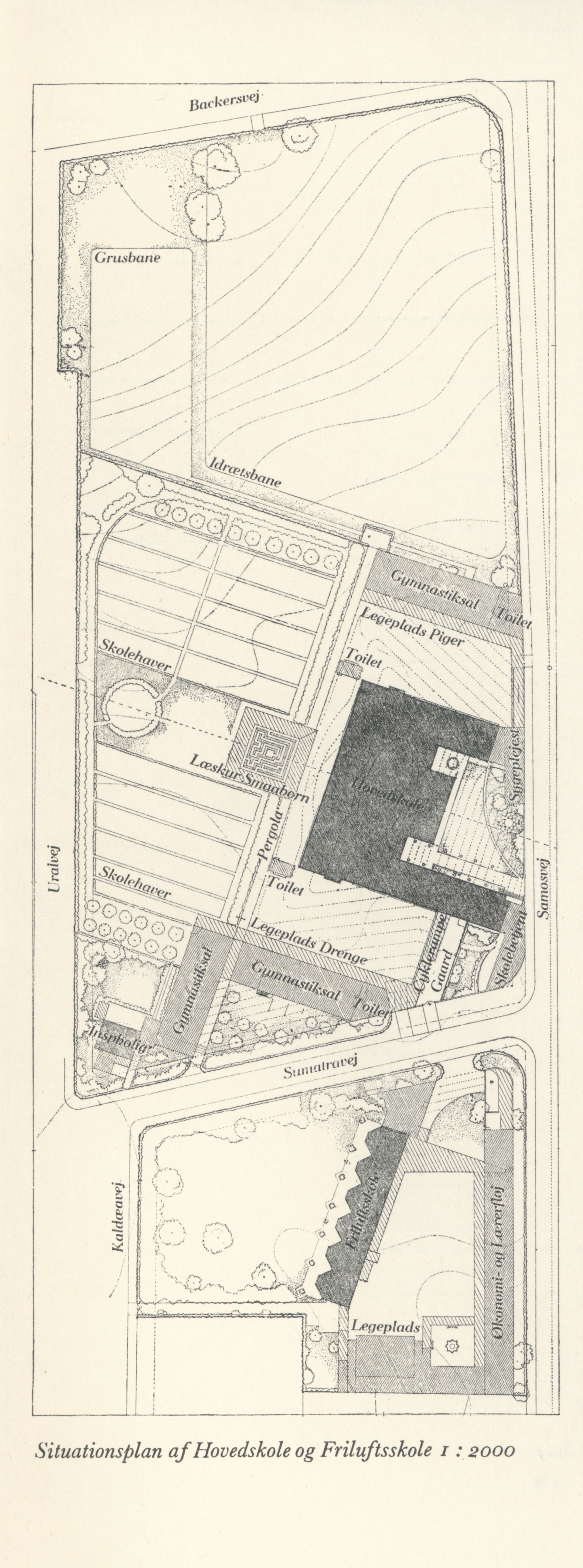

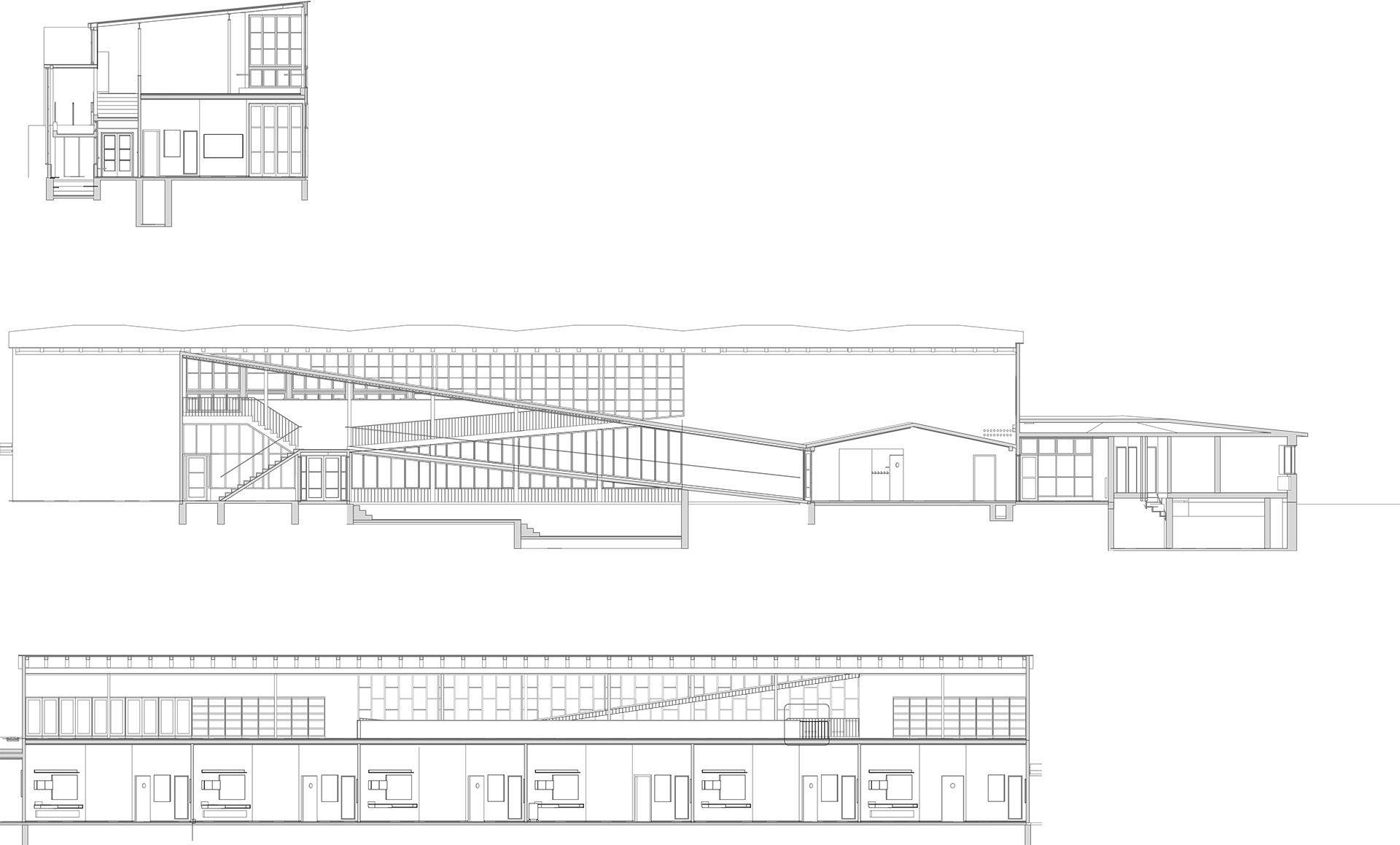

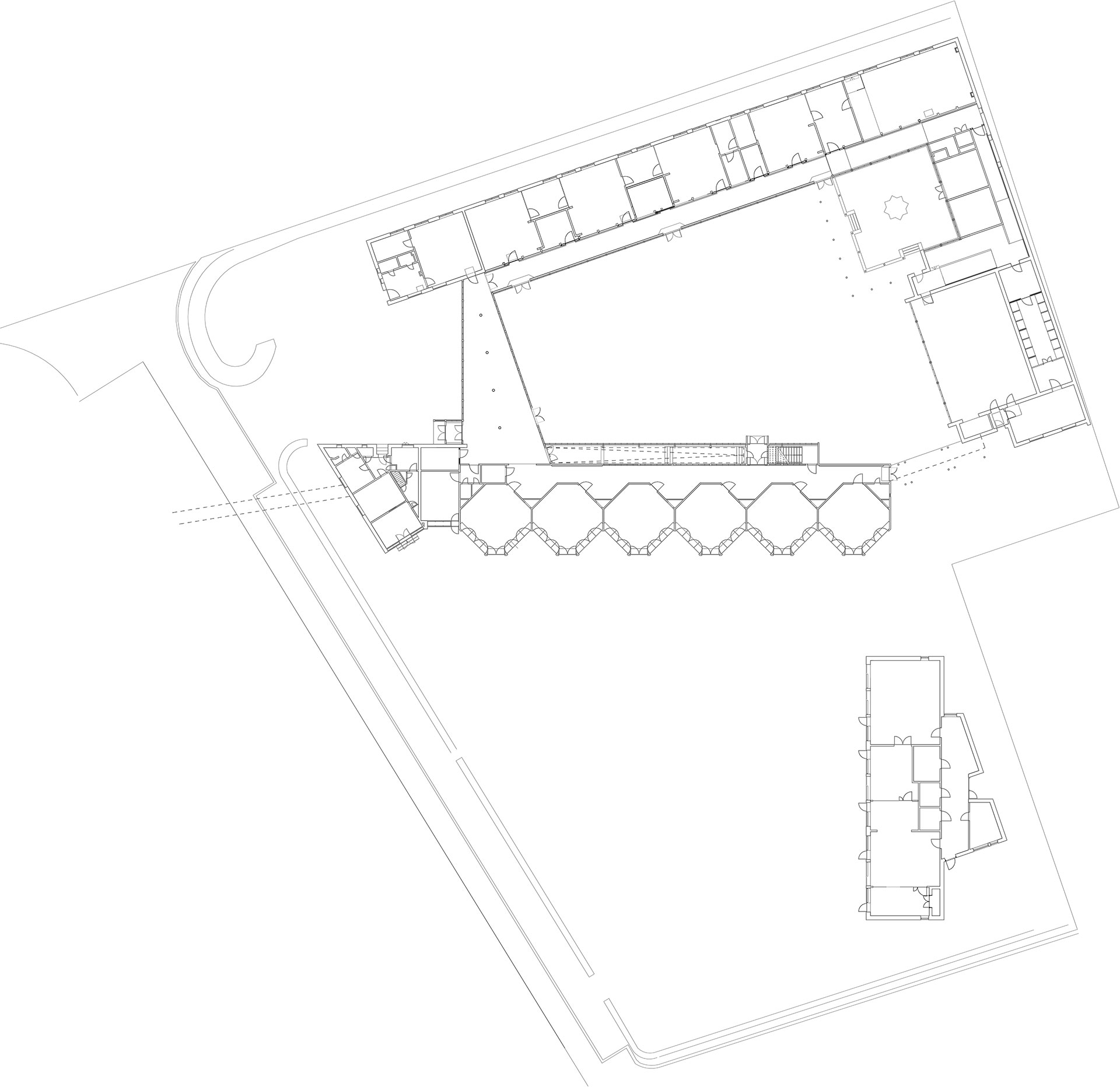

Friluftsskolen, which is a section of the Kaj Gottlob’s School at Sundet on Amager, is a fine exponent of the overall functionalist dream of using light and fresh air as crucial parts of a health-giving programme intended to bring health to the entire population here at the dawn of the Danish welfare society. The school was the first (and only) of its kind in Denmark, offering schooling and medical treatment to the sickly and tuberculous children of the poorer inner-city neighbourhoods, letting them lie arranged in rows in the large ‘reclining halls’ with façades made up of windows that opened to let in the light, creating an overall impression of a crystalline space – or gathering them around sun lamps in the ‘light therapy bath’. A large room was dedicated to handwashing: here, the next generation of industrial society was trained in frequent handwashing and tooth brushing around large sinks (the school originally had a total of 144 sinks). Ceramic tiles, linoleum and dafoleum (cast asphalt) floors, veneered doors, plastered walls painted in colours from Le Corbusier’s colour palette, glass façades and ingenious window systems that could be opened to provide natural ventilation were all details that fit in naturally with the architecture of this new age – one where the various functions were also clearly separated and grouped around a large internal, irregular courtyard. A southern wing contained six pavilion-like general classrooms (with the reclining hall on the first floor), a northern wing held rooms dedicated to health and hygiene, and finally a building to the east was used for treatment and gymnastics. For a child brought up in the crowded blocks and backyards of Denmark’s inner-city neighbourhoods, this must have seemed a wonderfully bright and strangely modern world.

Peter Thule Kristensen

Architect MAA, dr.phil., Ph.D. and professor at The Royal Danish Academy of fine Arts

Facts

Complete renovation of Friluftsskolen

Samosvej 52, 2300 København S

Architects: Nøhr & Sigsgaard

Team: Berit Thorup (project manager), Jacob Ingvartsen, Lars Møller Andersen, Peter Vegge, Peter Fisker, Jeppe Lindgaard

Client: Byggeri København

Engineers: Niras

Landscape architects: LYTT Architecture

Interior: Nøhr & Sigsgaard

Conservator: Københavns Konservator

Colour consultant: Caroline Krag

Preliminary studies: Varmings Tegnestue (evaluation)

Completed: 2021

Original building

Architect: Kaj Gottlob

Completed: 1938

Issue

The article was first published in Arkitekten 06/21.

Translation

This article was translated from Danish by René Lauritsen

ANNONCE

Ground floor plan. Drawing: Nøhr & Sigsgaard

Photo: Laura Stamer

The Friluftsskolen was a Danish response to a general reform movement centred around so-called open-air schools (known as Waldschulen in German) created mainly with inner-city children in mind. The movement saw its beginning around the turn of the century with educationalist Hermann Neufert’s Waldschule in Charlottenburg outside Berlin from 1904, and other examples quickly followed, of which Uffculme outside Birmingham from 1911 is particularly interesting because each individual classroom was set in a separate pavilion with glass façades that could be opened, just like in the school in Amager.

Another interesting role model for the Danish school is the open-air school built in 1935 in Suresnes outside Paris, designed by architects Eugène Beaudouin and Marcel Lods. Delegations from the City of Copenhagen, which included Kaj Gottlob among its participants, visited and thoroughly studied this school before the Friluftsskolen in Amager was designed. The school in Suresnes also had a large irregular courtyard in the middle and side corridors that led to classrooms housed in separate glass-covered pavilions, but on the whole most of the open-air schools of the time typically featured easy access to the outdoors, large glass sections that could be opened, and hygienic interiors inspired by hospitals.

Kaj Gottlob (1887–1976), like many of his generation, originally worked in a neoclassical style, but during the 1930s he became influenced by the modern movement, which he must have come across in various places – including Paris, where he designed the Danish Student House in 1930, roughly around the same time as Le Corbusier built his take on student accommodation, the Swiss Pavilion, in the same area. It is likely that Le Corbusier’s colour palette inspired Gottlob while designing the Friluftsskolen.

Friluftsskolen is a unique monument to an architectural movement and a new way of envisioning schools and education, and as such it was listed along with the rest of Skolen ved Sundet in 1990. While the listing was long overdue, it also led to the school’s staff feeling inconvenienced by working in a building where nothing could be changed. Thus, the complete renovation of the school has involved extensive negotiation between conservation authorities on the one hand and its users on the other. As a crucial element of this negotiation, the architects behind the project began by preparing a thorough evaluation – enacted in close concert with the stakeholders – which then formed a common basis for discussions and decisions during the subsequent renovation. The evaluation systematically reviewed all building parts, describing them on the basis of a three-tier approach: their original state and condition; their actual, recorded current state and condition; and finally recommendations on how to proceed. In this way, the project’s most important approaches and measures were identified and firmly negotiated before the actual design development began.

Photos: Laura Stamer

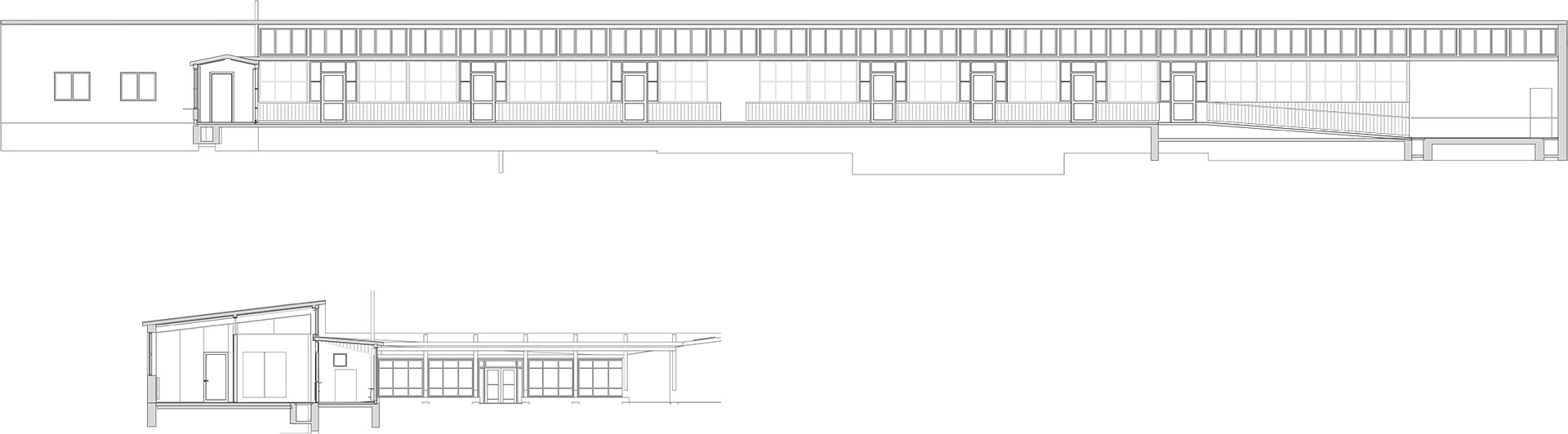

Overall, the renovation can be described as a mixture of two approaches: a restoration and reconstruction of the central rooms, not least the classrooms, reclining hall and corridors to reinstate the same look as the original rooms; and a more comprehensive remodelling, especially of the north wing’s former health rooms and dining hall, so that these spaces can be used for workshops, after-school recreation activities, music and exercise rooms.

The restoration is to a great extent based on the thorough evaluation process, including studies of the colours originally used in the building. Linoleum floors have been replaced in most places, and the original, richly varied colour scheme has been reconstructed. Instead of the original oil paints and distemper, a modern silicate paint was used instead. In the hallways by the classrooms, the silicate paint has been given an extra coat of floor varnish up to chest height, making the lower part of the wall glossy and more dirt-repellent. Each of the six octagonal classrooms in the south wing creates a niche in the hallway, which is now painted the same colour as the classroom behind it. Thus, pupils can easily identify their own classroom from the hallway.

At the same time, the use of acoustic plaster on the ceilings in classrooms and common areas made it possible to avoid the use of visible acoustic panels, which would have spoiled the rooms, and in the north wing some of the original beams have been exposed. The glass façades have been renovated so that they can still be opened, thus avoiding the use of mechanical ventilation now so widespread within contemporary school buildings. At the same time, the architects, together with lamp manufacturer Louis Poulsen, have developed new spherical acrylic pendants reminiscent of the old glass pendants. Thus, the surfaces on walls, floors, ceilings and light fixtures possess the same character and aesthetic originally found in the building.

A particular highlight is the re-establishment of the large reclining hall above the classrooms, which at one point was at risk of being subdivided. Here, the original red asphalt floor has been replaced by a moulded rubber floor which now makes the room usable as a grand, unheated exercise room, one which also provides access to pupils in wheelchairs by way of an original and spectacular ramp. In the north wing, a slightly more radical approach has been taken by subdividing the former dining hall, sink room and light therapy room into classrooms dedicated to specific subjects as well as a music room. The subdivision was carried out using simple glass walls and free-standing, linoleum-clad wall boxes that can, in principle, be dismantled again.

In this complete renovation, the architects cleaned up the building thoroughly, making the majority of the rooms look much sharper and with crisper details than before the renovation. This crispness also makes you aware of how a great deal of present-day school furniture can easily create a messy and haphazard look. Architecture such as this seems to require stringent and carefully planned furnishing, and the architects’ newly developed blackboard and wardrobe furniture for the Friluftsskolen fall slightly flat compared to Gottlob’s architecture. The yard, too – on which the architects should ideally have had greater influence than merely renovating an original drinking fountain in one corner – continues to appear cluttered with its recent, generic playground equipment.

Such minor quibbles do not change the fact that this is a very successful renovation: the building’s original qualities have been brought to light again while accommodating the users’ needs to be able to use the rooms in up-to-date ways – not least as a result of extensive negotiation work. During a tour, the restoration architect said that after the renovation, one of the users was moved to tears by how beautiful it had become. As an architect, you cannot hope for greater praise.